Oral Histories

|

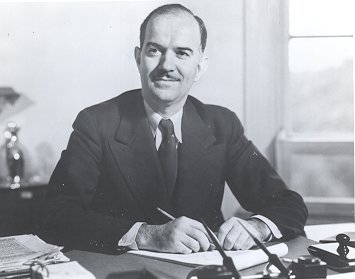

Merrill G. Murray, circa 1940. SSA History Archives |

Merrill Murray was an adviser to the Committee on Economic Security in 1934 during its development of the initial proposals for the Social Security Act. He worked on the unemployment compensation provisions of the bill.

Following passage of the Social Security Act, Murray went to work for the Department of Labor, then for the Social Security Board, then for the War Department, then for the Social Security Board again, and finally, back to the Department of Labor, where he ended his federal career in 1963. From 2/16/36 until 11/5/45, and then again from 9/1/48 to 8/20/49, Murrary worked for the Social Security Board, primarily in the Bureau of Unemployment Compensation.

HISTORICAL INTERVIEW WITH MERRILL G. MURRAY March 14, 1966 By: Abe Bortz, Historian Interviewer: We were involved with the work of the Committee on Economic Security. How did you first become associated with it? Mr. Murray: Well, I was at the time Director of the Minnesota State Employment Service and I had recently finished a book on which I collaborated with Bryce M. Stewart, who was heading the unemployment insurance part of the Committee of staff on the Committee on Economic Security, and he telegraphed me and asked me if I'd come down and join the staff. Interviewer: Did you now him previously? Mr. Murray: Yes, he had collaborated with me on this book, actually four authors did. For instance, his part was on the historical background on unemployment insurance. So through having met me there he asked me to come down and be his principal assistant. Interviewer: Did he come down very often to Washington? Mr. Murray: He spent a good deal of his time there after his appointment until the later part of the time. But my recollection is that although he was Research Director for the Industrial Relations Council, he spent most of his time in Washington during those three months. I came down early in September. Interviewer: What were you supposed -- or, did you have particular instructions? Or Mr. Murray: Well, the staff was divided up into several groups, and Bryce Stewart was in charge of planning the unemployment insurance legislation. In addition to myself, he brought down Gladys Friedman from his staff in New York. Then I think perhaps Witte who hired W.R. Williamson of Travelers Life Insurance to come in to be the actuary on unemployment insurance. Robert Nathan served on a part-time basis to make the unemployment estimates for us, and Mr. Fred Jahn, who had been working on social insurance for Reinhard Hohaus, Actuary at the Metropolitan, was hired by me as my main assistant. I worked with him and Miss Friedman particularly on legislation. What we were supposed to do was to prepare our own ideas as to what the Federal legislation should be on unemployment insurance, and prepare supporting material. And as the work of the committee got under way, it was a matter of meeting with the Technical Board meeting and answering what could be done on this or that question. Interviewer: Did you come in with any preconceived ideas of what -- Mr. Murray: Well, yes, I had made this analysis while I was at the University of Minnesota in 1932-1933. I was hired to work up a plan of unemployment insurance for Minnesota. And, working with Professor Alvin H. Hansen, we had developed a plan which we called A New Plan for Unemployment Reserves. It was a modification of the Wisconsin plan which had been on an individual employer basis. Our idea was to develop industry funds with the thought that contribution rates would be varied by industry rather than by individual employers. This plan was taken up by Governor Floyd B. Olson and we drafted a bill and he introduced it into the State Legislature there. But, in the course of discussion of that and further reading and work on another book on unemployment insurance, Mr. Hansen and I modified our ideas a great deal and became more and more convinced that pooling of the risk of unemployment was the thing; that unemployment was largely beyond the control of the individual employers, so we became more in favor of a pooled fund. Interviewer: Now, how about their pushing at the -- in regard to a national system? Mr. Murray: Well, then we also felt or became convinced that the general unemployment throughout the country - that this was really a national problem rather than a State problem. My experience in Minnesota where the Governor had me loaned to work the bill through the legislature, was that it would be practically impossible to get laws on an individual State basis - because the cost would be such a handicap to employers in competing with employers in other States. So, it was a combination of the realization that you can only get action through the Federal Government and that it ought to be in a national system. Interviewer: You looked at it them - this is, - I am just asking, in other words, as you came down and you knew you had the job, were you looking at it as a pure Federal system or -- Mr. Murray: I would say that my own thinking was coming pretty largely around to that. Interviewer: And then when you came, were any specific instructions or suggestions made as to within what range you should work, or what possibilities - or were you just -- Mr. Murray: Well, at the beginning, I don't recollect that there were. Bryce Stewart had very positive ideas, also, and he began to promote them. He leaned more toward industry funds, but on a national basis. He had been Director of the Canadian Employment Service and had a background of Canadian and British thinking that made him think in terms of a national system, but he still leaned toward the idea of industry funds. Interviewer: What was the first - Mr. Murray: Well, I don't remember too clearly the sequence of events, but very soon the big argument became whether to have a national system or a Federal-State system; and there was before us a pattern that had been worked out in the preceding year in the Wagner-Lewis bill for a Federal-State system that was largely along the lines of what was finally enacted, and so -- Interviewer: Hadn't the President sort of given some direction to that by -- Mr. Murray: We weren't aware of that. I know Witte in his book says the president had given specific instructions along this line, but we weren't aware. I don't remember that we were aware of this until the national conference was called in November at which he made it quite clear that he favored a Federal-State system. Interviewer: However, didn't most of those experts who came in at the meeting favor a national system? Mr. Murray: Yes, that's right. They include I think such people as Paul Douglas. I believe Leiserson was at that meeting. Interviewer: Yes, he was there, too. Mr. Murray: Most of the 15 or 20 experts who were on the unemployment insurance at this national meeting were for a Federal system. Interviewer: Were you at the same time asked or told to work on the other approach? Mr. Murray: Well, we had done all right before the national conference - had been presenting papers, working up papers on the pros and cons of a Federal system vs a Federal-State system; and these were discussed both with the Technical Committee and the Advisory Council. Stewart and I sat in on these sessions, and the Advisory Council, - Stewart had particular influence with the employers and sold them his ideas for this national system on an industry basis. Well, -- I would say that Stewart never gave up on a national system, but at some time I think after this national conference in November, the idea was injected of what they call a substantive plan, which would be that the Federal Government would collect the tax to be distributed back to the States in proportion to what the employers in the State had contributed. Interviewer: Is that the same one they sometimes called the grant-in-aid? Mr. Murray: Yeah, grant-in-aid. Since the President had put thumbs down on a national system, then the battleground switched to whether it should be this grant-in-aid system or a tax offset plan, and the essence of the difference between them. Those who had favored a Federal system swung to the subsidy system because from a constitutional standpoint there was enough precedent that it was thought that some real standards could be written into such a bill. Whereas those who favored the grant-in-aid plan were very skittish of putting any standards in, and, in fact, I think probably most of those on that side were against giving the States standards on the principle of States rights -- Interviewer: What role then did those who advocated the Wisconsin system play in this? In this error -- Mr. Murray: Well, I would say that they had been sidetracked in a way. Witte was from Wisconsin and Altmeyer was Assistant Secretary of Labor and Chairman of the Technical Board, and they were both from Wisconsin and both had worked on the Wisconsin Act. Altmeyer and Witte had been in the State government in Wisconsin and there was close collaboration between the Governor and the Department of Economics at the University, so that Paul Raushenbush and his wife, Elizabeth Brandeis, and the Professor of Taxation at Wisconsin -- Groves, Harold Groves, had worked on the Wisconsin bill and in general it followed up to Commons' ideas on stabilization of employment. So they were imbued with the philosophy of giving the employer maximum responsibility with the idea that unemployment insurance could be used to stabilize employment, and also they had the very strong feeling that the States had primary responsibility in this field. In other words, they looked on Federal legislation mainly as a mechanism of getting legislation passed, but I felt that the responsibility for unemployment lay primarily with the States. Interviewer: Was this other hope of experimentation a legitimate one, or you think that because the President did not indicate that he wanted that? Now, I don't know whether that was -- Mr. Murray: Well, I think that may have been a rationalization, although there were so many ideas as to the form unemployment insurance should take that I think there was some genuine feeling that different ideas should be tried out in different States so that you can find out which idea worked best. For instance, some States could try out pooled funds in which there was experience rating and other States the individual employer reserves, and then whichever system proved to be the best could prevail. Interviewer: Was there sufficient evidence, or experience, for us to do our own or foreign -- Mr. Murray: There was a great deal known about foreign experience. Bryce Stewart had brought out very comprehensive studies of unemployment insurance in Great Britain, Belgium, Switzerland, and Germany, which had been studied by the students of it. There also were some precedents, and some private plans have been initiated in this country by employers so that the general pattern of unemployment insurance was pretty well understood. But there were ideas that we shouldn't just copy from Great Britain or other European countries. For instance, it was believed that the wage structure was so greatly varied in this country; there was much greater variation in wage structure in those days than there is today between States because of lack of organization of labor, so that, flat benefit systems such as England had just would not be workable in this country. You'd have to cut rates -- if we had a national system -- you would have to cut rates so low that they would be too low in New York - or be too high in Alabama. Dealing on a State basis, it was felt again the States could then - if they were given leeway -- could fit their benefit structures to the wage structure in their States -- Interviewer: Once you moved away from the national plan and then the issue seemed to come down between the subsidy or grant-in-aid against the Wagner-Lewis tax offset, what was the final influence that pushed it over? Was the Advisory Council - Mr. Murray: I would say that the Advisory Council, I think became, more of a figurehead. Let me put it this way. I think that Witte and those in real control got to feeling that the Advisory Council was something of a nuisance and standing in the way of their getting something done. Because the Council wanted to really deliberate and Witte felt there wasn't time for this. There was increasing estrangement between Witte and Stewart as far as the staff was concerned and between Witte and the leadership of the Advisory Council so that Witte progressively ignored both. Bryce Stewart got sort of at odds with Witte so he picked up and took his whole staff to New York. I think that was late in November, maybe early in December. There was a fairly comprehensive report was worked up very much in line with our own thinking which, so far as recommendations were concerned, came out for a national system but said that if this isn't acceptable then; we favored a subsidy system - a grant-in-aid system. This report, according to Witte's book, was brought in too late to be considered. Well, actually, I don't think it would have had any consideration anyway. Interviewer: Did you or Mr. Stewart ever have the opportunity of presenting the arguments verbally to the Cabinet Committee? Mr. Murray: Not directly to the Cabinet Committee. Now Stewart may have had, but I never went before the Cabinet Committee. Interviewer: Well, was Mr. Witte the only Cabinet -- Mr. Murray: We met with the Technical Board. Interviewer: You did meet with the Technical Board? Mr. Murray: Oh, yes, we did meet constantly with them. Interviewer: There was disagreement there between the Technical Board, and the Committee. Mr. Murray: Well, no, I would say there -- not so much between the Technical Board and the Committee, but between the Advisory Council and the Committee. The Technical Board was headed by Altmeyer who was working closely with Witte and was pretty much in agreement with him on ideas. Now, there were people in the Technical Board, Like Alvin Hansen -- Alvin Hansen was on the Federal Reserve Board at that time - who disagreed with what was going on. Interviewer: What about some of the others - like Viner? Was -- Mr. Murray: Well, now my only contact with Viner was in connection with a subcommittee they set up on the financing -- Viner, Alvin Hansen, and Jensen. There the discussion was much more -- Interviewer: Was that more on the technical details? Mr. Murray: Yes. It was on how they expected to raise the taxable rate set at a maximum of 3 percent. And they were concerned about this hitting industry all at once, so then they considered this step-up plan but they wanted to gear it to the increase in industrial production. Actually, Congress put it on the basis of first year 1 percent, next year 2 percent, and next year 3 percent. Interviewer: Would you call the kind of system the major crisis of the Committee? Mr. Murray: I think so. I think that in discussing which kind of a plan to have, there was a great deal of discussion of constitutional questions. Interviewer: Well, didn't they suggest, for example, that even if the law was declared unconstitutional that -- Mr. Murray: The States could go on. Interviewer: Yes. Mr. Murray: Because we felt that the State laws would hold up under the police powers of the States. Interviewer: What about the issue of the size of the firms? Was that much of a problem? Mr. Murray: I don't recall that there was very much discussion of it. It was generally recognized that at the beginning small employers had to be exempted. Interviewer: Of course they didn't do that in the old-age insurance. Mr. Murray: Oh, no, and I don't remember any cost discussion of this. Interviewer: Was there ever any feeling that the two taxes might be combined to simplify administrative problems so that it would be necessary to have two systems - that's finally -- Mr. Murray: Well, we argued that. Interviewer: Because there are some similarities, even the tax base that you use, and the -- Mr. Murray: Well, there was similarity in that the tax base and the coverage was similar, which simplified reporting for employers. The Committee started out, I mean in their recommendations -- you see, they had in mind very wide coverage for unemployment insurance. They didn't recommend any exemptions -- there were exemptions in many groups, including agriculture or domestic, in the Act because of the pressures on Congress. The only thing the Committee recommended was to have some limitation on the size of the firm. And the reason that the coverage was one or more from the beginning in old-age insurance was because of recognition that over a man's life time he might work for small and large employers and wouldn't have any continuity of his employment, but in unemployment insurance with his qualifications being based on a relatively short period, that there wouldn't be many who would work part of the time for small employers and part of the time for large employers, so it was felt there wouldn't be any great loss in not covering the small employers there wouldn't be any great loss in not covering the small employers initially. But it was expected that after initial experience was gained, they would go to complete coverage. Interviewer: How about the problem of the reinsurance, possibly the fact that you have strong and weak States and you might exhaust funds? Mr. Murray: Well you know, as a matter of fact, I was surprised in looking over these papers that you dug out of the files that I had written a paper on reinsurance. I had forgotten all about it. Interviewer: What happened to that? Mr. Murray: It never got much attention in the early days. Interviewer: Well, it would be a way of getting around the problem of a national system because in that sense you're solving some of that. Mr. Murray: Yes, that was the reason that this was brought up as a possibility. Interviewer: Were there administrative problems too difficult -- Mr. Murray: Well -- Interviewer: That the poor States would soon be charged. Mr. Murray: The charge has always been that with a reinsurance plan that some States would take advantage of it. And you couldn't work up a plan without very tight controls which would take away all this freedom away from the States. I've seen memoranda written back in the early '40's and then on about reinsurance but it never became a real issue until the early 1950's. And then it was presented as an alternative to the so-called George Loan fund which had been enacted right after the war, which was a little familiar to the States -- if they got into financial difficulty. Interviewer: Almost because of the same thing that they don't have to repay otherwise. Mr. Murray: Well, they have to repay these loans. They get them interest free. And the argument has always been that this still keeps the State fully responsible for its own system since it's got to repay the bills some day. Interviewer: But, it never got very far then in that period? Mr. Murray: No, I don't remember it. I think it was one of these things that when it became apparent that it would be a Federal-State system that this was thrown in as one way of spreading the risk over the country but was never taken very seriously. Interviewer: How did they arrive at the $50 a week basis for a base? For taxes? Mr. Murray: Well, originally the unemployment insurance part of the tax was based on total payroll and this was causing confusion among employers, because only the first $3,000 out of each worker's pay was taxed under the old-age insurance system. So when the 1939 Amendments of the Social Security Act were presented to Congress the Social Security Board recommended that the tax be put on the same basis from unemployment insurance, namely, $3,000. At that time, the first $3,000 still collected somewhere between 95 and 98 percent of the total payrolls -- it still taxed 95 to 98 percent of the payrolls. Interviewer: What was - now, of course, looking at it backwards - but how did they originally arrive at that figure? Mr. Murray: At the $3,000? Interviewer: Yes. Mr. Murray: Well, that was arrived at in connection with the old-age insurance. Interviewer: Well, I can't find the basis for that either. I've checked back. I know they started with the $250 a month, and originally they were going to exclude anybody who made over that. Then, of course, Congress changed it to merely multiplying 12 by $250, but even the original one, I'm having difficulty finding where they got the $250 unless it comes in an earlier bill -- Wagner bill. Mr. Murray: I don't think so. I think that probably it was based on the fact that $250 was awfully good pay even for a white collar man. Interviewer: Why didn't they take $300, for example, the $300 is in the railroad retirement. Mr. Murray: Well, the railroad workers were higher paid and I think that it was felt that this would take in the great majority and -- Interviewer: It was based on some -- Mr. Murray: Yes, it was based on some knowledge of earnings. Interviewer: I noticed there was some discussion, too, over the method of collecting, the possibility of using a stamp book here. Mr. Murray: Yes. That was very seriously considered and extensive memoranda were written both before and after the Act was passed on the possibility of a stamp system. But increasingly it was realized that with the taxes based on wages it would be more complex to collect on the stamp basis because of the great variety of denominations of stamps that there would have to be. Interestingly enough, I think the first year I was in the Analysis Division of Old-Age Insurance in 1937 and 1938 - Rodney Boyce - you know him, and Stock Meters came down and had a number of sessions with me on this. Interviewer: I don't know whether I'm covering the most important area, but I know as a basis of much of the discussion over unemployment insurance or compensation, the program was looked at in terms of being a device to aid in times of comparative prosperity. Was that the whole view? Was there any idea, possibly of taking care of severe recessions or real depressions? Mr. Murray: Yes. Personally, I felt there was. I felt that the Wisconsin Plan, which provided very limited duration of benefits, -- 10 weeks, -- seemed to be almost piddling. And so when I was working on a plan in Minnesota, I got the idea of a longer waiting period with an assumption that maybe for the first 3 or 4 weeks the person could get along without real hardship and the money that we saved from the large amount of short-term unemployment of that kind could be used to pay longer durations. Also, it would be necessary to go up to 4 percent of payrolls in contributions, we estimated - to pay a duration of about 40 weeks. It seemed to me that we had to get up in the neighborhood of 40 to 52 weeks to have a system that really worked. Interviewer: What about the problem of attempting that in a severe recession -- Mr. Murray: This was the idea. This was based on reserves being built up during periods of prosperity so that we could pay that kind of duration during the recession and then there was expectation that the duration of benefits during prosperity would be very short for most unemployed. Interviewer: What happened, incidentally, to the Minnesota Plan? Mr. Murray: Well, I think the one thing that did jettison it was the actuarial estimates which W.R. Williamson made - he made very conservative estimates and loaded into the estimates every factor he could think of; and on top of that just to be sure he hadn't overlooked anything, he put on another 30 percent loading factor. He came out with such short duration that the committee was just nonplused. They felt, well, this just pulls the rug out from under on having a system at all because his estimates were that with the 3 percent tax - and they felt that was about as much as could be asked or imposed and leave room for old-age insurance experience and with a four-week waiting period, the most that could be paid would be ten weeks of benefits. And the committee fudged a little bit on that and based on 1922-30 experience that 15 weeks could be paid. Interviewer: That would eliminate all the worst years, would it? That would make it easier. Mr. Murray: Yes, that was based from 1922 to 1930. Interviewer: We hadn't reached the depths yet? Mr. Murray: No, but then at least they could publish these estimates and say that you could pay 15 or even 16 weeks if you - well, there again, it was a matter of fudging a little bit. But I think then, talking about unemployment insurance as a first line of the defense, there was a good deal of rationalization in it and this is all you could promise, and even then, it was recognized that it would do a lot of good because even in a depression a lot of unemployment is of less than 13 or 14 or 15 weeks' duration. And then in those days, of course, there was great faith in what could be done through public works. If you paid benefits for three months, this would give time to get a public works program under way, and the worker exhausting benefits could be put on work relief at least. Interviewer: Of course, you were also inhibited in that sense that you were trying to start something in the depths of depression which would automatically limit the amount that you could tax payroll, too. So, you had that additional handicap. In that connection, how much thought and how much discussion and controversy was there over employees' contributions? Mr. Murray: Well, this was thoroughly discussed in the Advisory Council. Labor was opposed to it. Interviewer: When you say labor, is that conflicting -- that is that the national AFL was opposed to it but that there were some State organizations that were not opposed to it? Mr. Murray: When you come to the representation on the Council itself -- Interviewer: Where you had that subcommittee on unemployment insurance - I think it was Leeds, Folsom, Green, Scharrenberg, Winant, and Kellogg. That's of the Advisory Council. Mr. Murray: Yes -- Folsom was an employer -- Interviewer: You have Green and Scharrenberg. Mr. Murray: I think Folsom favored employee contributions at that time. Well, Green and Scharrenberg, the labor representatives did not. -- Scharrenberg, wasn't he from Wisconsin? Interviewer: Yes. Mr. Murray: Wisconsin had passed this employer financed law that put all of the responsibility on the employer, so he was against employee contributions from the standpoint of that's the way it was in his State. Green had opposed to unemployment insurance altogether -- and came around to it very reluctantly, and so I think he also opposed employee contributions because it got labor paying for a program it was somewhat afraid of. Interviewer: You had Leeds, Ohl and Governor Winant. Mr. Murray: But this also was discussed and came to a vote in the whole Council. I remember that meeting very well. Interviewer: What was the view of the staff as well as the Technical Board? Mr. Murray: Well, I believed in employee contributions and I think Bryce Stewart did. I guess the staff generally was in favor of them, but of course, when you've got a system such as was decided upon, this tax offset system made employee contributions impractical on a Federal basis, because where the experience ran particularly high employee contributions was very difficult to administer. Now, they were still promoted. You see, we promoted employee contributions out in the States. Interviewer: A number of States did adopt them? Mr. Murray: Yes, but you see you could hardly have a 90 percent offset against an employee tax -- that's three-tenths of a percent, which is pretty small. Interviewer: What validity do you think is there in that argument that whereas the employer had a way out - the tax in a sense could be passed off or it would be included in the cost of production whereas the employee ultimately would be paying for it anyway. Mr. Murray: Well, I think there's something to that, although I think that at that time this was pretty much taken for granted, - let's put it that way: The employer contribution would either be passed on to the worker, the employer's contribution would be, so why should he pay an employee contribution. Or else the employer could pass this on to the consumer, - well, the employee couldn't do that. And also if it was passed on to the consumer, the employee was a consumer so why should he pay? Interviewer: How far did this go -- or did you think it had much chance at the time of passing? I'm speaking only of the work of the Committee. Mr. Murray: Well, it just didn't fit into the tax offset plan, so although I think the staff was for it, it was thrown aside. Interviewer: How about the Government contribution idea? Mr. Murray: I don't think that got any consideration. Interviewer: It didn't get any at all. I guess only Mr. Kellogg was the only one that kept insisting on the -- Mr. Murray: Yes, I guess there was a little bit, but certainly we didn't push it. The idea was that the Government was so heavily involved in relief. Let it take over the relief task and the insurance be financed by industry and maybe by the employers and employees. Interviewer: What about the problem of standards? That is, the hope that in some way or other - of forcing the States to -- Mr. Murray: Well, that, I would say, was one of the main motivations behind the subsidy. The subsidy idea was that from the constitutional standpoint, standards could be written in where it was feared from the constitutional standpoint they couldn't under the tax offset plan - although the original Wagner-Lewis Bill which was introduced the preceding year had standards in it. But, in the meantime, there was the adverse railroad retirement Supreme Court decision which put the fear of the Supreme court in the hearts of everybody working on this. Interviewer: I notice that something developed here which later proved to be one of the big problems, that is, the separation of unemployment compensation from the -- Mr. Murray: Old-Age insurance. Interviewer: Or from the other, from the USES. Mr. Murray: Oh, from the United States Employment Service. Well, everybody working on the unemployment insurance side just took it for granted that there had to be a close connection with the Employment Service. They had the precedent of the systems in Europe, particularly in the British and German systems, where not only claims were taken but the benefit payments were actually made in the employment office. The main idea was the application of the so-called work test, that if a worker filed a claim in the employment office, then he would be exposed to the jobs that were available. The talk was that the important thing was employment instead of unemployment insurance and, therefore, there should be a maximum effort to get a man back to work. Interviewer: You were saying that the Europeans looked at it as two parts of one system. That developed to be one of the biggest headaches later because it was claimed that they couldn't put them together since in the process one or the other would tend to dominate the other, and at the expense of - Mr. Murray: We heard nothing about this at the time. And, in England, they were under the same administration. And Germany, - they had a separate institution of unemployment insurance and employment service. The employment service had been organized first over there as well as here, but had not built up a vested interest evidently in England like they had here, where there was opposition to joining the two programs. I think Frank Persons, the Director of the United States Employment Service, had a lot to do with this -- making a real issue out of whether the two should be together. He believed, I think sincerely -- I don't think it was just a matter of bureaucracy, although I felt so at the time -- he felt that the employment service should be kept distinct. So, he bucked any consolidation of the two. An agreement was worked out for maximum coordination between the Social Security Board and Miss Frances Perkins, the Secretary of Labor, but it was almost over Persons' dead body. He believed that the employment service would be submerged and he thought of the employment service as a great institution that should -- Interviewer: Of course, that couldn't be foreseen at the time you were working because you did assume that it would all be in the Department of Labor; but then, when Congress decided to make the social Security Board an independent agency, in a sense it created problems. Mr. Murray: So the thought was then we ought to bring the employment service over. Interviewer: After the bill was introduced - you know the Wagner-Lewis-Doughton bill, what role did you play? Mr. Murray: I didn't have a great deal to do with it. I followed it. But Tom Eliot, the Assistant Solicitor of Labor, carried the ball up on the Hill; and he was a young fellow feeling his oats and didn't need to consult very much with the experts. So we had very little to do with legislation. You see, the staff was disbanded -- well, I guess there just weren't funds. They cut down the staff as soon as the committee made its report. And I was largely absorbed with working on State legislation so that I didn't do much more than follow what was happening on the Hill and, even then, not very closely. Interviewer: Were you then already beginning to get requests from the States? Were you encouraging them? Mr. Murray: Oh yes. This was on a request basis up to this time because we didn't have a law under consideration. In 1933 probably three-fourths of the States had bills, so requests began to come in for technical help on them. The Committee sent its report to the President just before Christmas, during the Christmas holidays. Arthur Altmeyer had Paul Raushenbush came down, who had a large part in drafting the Wisconsin Bill. Those two and I worked out the draft bill, or two draft bills - one for a pooled fund with experience rating, and one for a Wisconsin-type employer account bill, and so we had these mimeographed. These were available when a request came for information - these were sent out. Then if a request for somebody to come out and explain this to them, I went out. I didn't make many trips before the Act was passed, just in a few States, but I was also working on correspondence on the Townsend Plan, -- Interviewer: Miscellaneous duties. Mr. Murray: Whatever had to be done. Interviewer: Of course, Mr. Witte was only making -- Mr. Murray: Well, he left very shortly - as soon as the -- Interviewer: After the report was - went back Mr. Murray: Well, he of course went back after the Congressional testimony. But then, I guess he was there most of the spring. Yes, he was there through most of the time the bill was under consideration. As I say, there was just a skeleton staff left outside of Witte, and Tom Eliot who had carried the ball on the bill. Interviewer: You were never called in at the executive sessions? Mr. Murray: No, I had nothing to do with it. Interviewer: Then, of course, Mr. Harris served for some time and then he left. Then, what? Mr. Murray: Well, after the bill was passed, the staff was whittled down to just a small group to organize the papers and write the "Social Security of America", a symposium of all the staff reports. I had charge of writing the unemployment insurance part of that; it was in the summer of 1935. Interviewer: Did you work at all in helping to set up the Board itself? Mr. Murray: Well, yes. In the first place, Altmeyer used me that summer to work up a budget. Interviewer: Ahuh, that must have been quite a problem. What aim did you use to go on? What criteria did you have to -- Mr. Murray: We didn't have any. It was largely guesswork. But we knew we had three broad areas to cover - unemployment insurance, old-age insurance, and public assistance. There would be a Bureau for each of them, and so we guessed at what staff these Bureaus would need. This was, of course, little to do the first year so far as old-age insurance was concerned. It would be in the planning stage, so not a great deal was worked into the budget for that. So, we came up with $1 million and thought we had asked for an awful lot of money. Interviewer: I suppose it was in those days. Mr. Murray: So, then, when the Board was organized, there was actually -- Interviewer: Had you then moved over? Mr. Murray: Altmeyer brought me on over. The Board had no appropriation. The appropriation got caught in the Huey Long filibuster. So I was kept on the Federal Emergency Relief payroll, which had actually financed the staff of the Committee on Economic Security, and Wilbur Cohen and one or two secretaries. And we were the staff of the Board. And for a while there we were the only staff. There were very long arguments by the Board. They got deadlocked over who should head up the Bureau of -- no, I guess it was who would be the Executive Director of the Board. Interviewer: Between Seidemann and Bane? Mr. Murray: And Bane, - and finally compromised by Seidemann handling the -- Interviewer: the coordinated - Mr. Murray: Coordination. Bane the administrative end. Seidemann concentrated on planning the old-age insurance set-up. And then they began to recruit staff. Interviewer: Where were you then, physically? Mr. Murray: In the Department of Labor. Interviewer: They gave you - provided you with some offices and furniture? Mr. Murray: The Social Security Board had offices, and we occupied part of the floor there. Then I borrowed a few people -- got Cornelius R.P. Cochran who was later with the Bureau of Old-Age Insurance. He came over from NRA - you see, NRA was declared unconstitutional so here were, were some people - some available people. Gladys Friedman came down from Bryce Stewart's office. I got one man from Colorado, but I didn't know at the time he was a cripple. I had to have a staff that could travel so that didn't work out. During the fall, I was by myself for several months. Cohen was handling internal correspondence. So I was called Director of Federal-State Relations, and I was handling or trying to cover the waterfront on advising States both on unemployment insurance and old-age assistance, and everything else. I couldn't pretend to do all that had to be done, because we were flooded with requests then for help. Interviewer: Well then they started looking and I suppose they did secure the other Bureau Directors; Mr. Wagenet came in, and then Jane Hoey and Mr. Murray: Yes, then by February when we finally got an appropriation, there was a skeleton staff. Interviewer: What was your job then? Mr. Murray: Well, the big thing then was to get laws passed in States, as far as unemployment insurance was concerned. So I concentrated on that. I didn't know what my title was, Associate Director or what, but Wagenet eventually organized it so there was a division of legislative aid and a division of administrative aid, and he brought Fred Croxton in to head that. But, for the first two years, or the next 1 ½ years I guess you'd say, there was a crisis every moment on working with States to help them get legislation, so that I had to devote my entire time to do that. Interviewer: Was that chiefly traveling? Mr. Murray: A great deal of it. I got some staff but there wasn't a chance to train them thoroughly enough. They had to lean on me a great deal, so if they were out, I was constantly getting long distance calls and telegrams and so on - and where an important State battle developed, I would go out personally. I covered I expect half the States. Interviewer: Were you obviously in the process? I mean in the sense in trying to influence, a Mr. Murray: We did, but I mean the policy was to go out only on request, such as the Governor. Most of the States had nobody in the State who was an expert on the subject, so they'd write in to the Social Security Board, "Will you send somebody out to help us?" And, usually, the process would be I'd go and talk with the Governor. I'd go first to the Governor and talk things over with him, and then he'd ask me to work with either some staff person, or the Department of Labor, or with a committee on the legislature. We had these draft bills and I no doubt had some of my own ideas. But, if they had different ideas, there was the matter of getting them the best technical advice. Interviewer: How long did you stay in those - what I'm thinking did you go all the way through the legislative battle? Mr. Murray: No, no, I would go out and be out there for a day or two and then come back. I think the longest stay I made was in the summer in Idaho. I was out there for a week or ten days. We went through the whole process of drafting the bill - the turning out of it there. There was quite a conservative lawyer the governor had me work with and I had to battle the bill through with him, and then a special session of the legislature was called and I was called in to talk before the committees there. So, in that case I was out maybe ten days or two weeks. But normally, it would be a matter of running out and then running back. I guess, for instance, in Ohio I went out two or three times before the bill was passed. I'd go out for a Committee Hearing, for a session with the Governor, and that sort of thing. Interviewer: How influential a role was there - I mean, did you find out that your influence was considerable? Mr. Murray: I think that certainly the draft bills had a great deal of influence and many features of the State's laws were patterned after the draft bill. In the latter stages, a number of States held off, hoping that the Supreme Court would rule unfavorably, and so they waited to the very last moment to call special sessions. So we had a rash of sessions in December of 1936 of States wanting to get under the wire. And those days were really hectic. And many of the States just took one of the two draft bills, whole hog, and put it through the legislature. They didn't have any choice - had maybe a two- or three- day session of the legislature and had to have something that was put through. But a number of the States had some informed people in them. And, I remember a few cases where the employers had major influence. Then, during this time, Frank B. Cliffe, of the General Electric Company developed what we called the Annual Wage Plan. His philosophy was that benefits should be based on a man's annual earnings. His real standard of living was based on his annual earnings; and, therefore benefit formulas should be based on annual earnings. He also argued this would be much simpler from a record keeping standpoint. He was assistant treasurer of, or, comptroller of the General Electric and legislators listened to him with great respect. His plan simplified administration and so on. So he got bills through in at least a half-dozen legislatures. Interviewer: What success did he have? Mr. Murray: Well, those laws have worked out, generally, to provide much smaller benefits. Interviewer: Smaller benefits? Mr. Murray: Even though they've greatly liberalized the formulas over what he was recommending, still the average benefits in those States are much less. Interviewer: Are there any particularly memorable episodes here in dealing with some of these - State legislatures - Mr. Murray: Well, -- I remember going to Nebraska. There they didn't have the unicameral legislature yet, and they had a joint session of the two Houses. The Governor asked me to explain the bill to them and then they threw it open for questions. I kept talking about - this bill being enacted to enable to States to pass legislation without fear of interstate competition. Some legislator called out, "Hell, it is a sledge hammer." That was a rather hostile crowd I was talking to. I remember that in two of those States in that tier of States -- Kansas was one of them -- where the lawyer for the main railway system in the State was the dominant figure in seeing what kind of bill they had because, at that time, railroad workers were covered for unemployment under the State's system. I also remember rather vividly working in Ohio because I went back there a number of times. Cliff and I battled it out before the Committee. They had had a commission so that they were very well informed and technical issues came up there. When it came to final passage in the Senate, I remember I had to call Washington and ask for an attorney to come out and help me. Interviewer: How about Paul Douglas who was considered, I assume, as an expert on wages and -- Mr. Murray: Well, he was invited down to this national conference in the fall of 1934. Interviewer: Yes, but that's about the Mr. Murray: Yes. Well, I think the Committee on Economic Security didn't call them in because they knew they'd just have that much more argument on their hands. Interviewer: Well, with that in mind, then, he didn't anticipate then having trouble with Mr. Stewart? Mr. Murray: I guess not. Interviewer: I mean what developed this - well, okay, it was something unforeseen? Mr. Murray: I just really don't know about that. I mean some of these things that went on in the higher councils I was not in on. Interviewer: I think we were talking about some of the problems you had going out into the States. Mr. Murray: Yes, it was - Interviewer: Of course, the program was just getting started then, wasn't it? And they had enough time to determine which particular type best fitted the State, so I guess - Mr. Murray: No. Actually, when you come right down to it, you can't vary a system very much to fit a particular State. The features of unemployment insurance are such that, well you might, for instance, gear the maximum benefits to the wage structure in the State; otherwise, I would say that there are no conditions peculiar to a State that require a different kind of system from one State to another. So it was largely a matter of dealing with political forces where there were people who happened to be in the State who knew something about the thing and that were influential. Then it was a matter of either working with them or trying to persuade the Governor and the legislature where they were wrong, where I felt they were wrong. I'm trying to run through the States to think of any particular things that developed. Interviewer: Were there places where they wanted to keep you out, or - Mr. Murray: No, there wasn't that attitude at all in those days. There was general recognition that they didn't know about unemployment insurance and any help they could get they were glad to get. So that even though in a State where they thought this was Federal dictation, they still asked for somebody to be sent in to help them. Interviewer: Well, this is still the period '36, isn't it, pretty much? Mr. Murray: Yes, by the end of 1936 all but two States had passed laws. As I say, in the last few days these bills were passed in a couple of days or so. Interviewer: What happened after the beginning of 1937? Mr. Murray: Well, then we began to concentrate on administration, and planning administration. We set up a Committee within the Bureau to plan procedures for the States and at that stage Fred Croxton was brought in because he had had a lot of administrative experience. And I began to feel that my mission was ended because I thought all the States had passed laws now, and there was nothing more to do in this area and I didn't know anything about administration. Of course, there have been constant amendments; you wouldn't recognize the original laws any more. Interviewer: Well, had you by that time gotten some of the feeling of this growing dispute between unemployment compensation and Frank Persons'- Mr. Murray: You mean the employment service? I was very conscious of that. I had a personal run-in with Persons by speaking on the same platform out in San Francisco before the social workers (It was either San Francisco or the State social work organization, I forget which). Persons spoke first, and the whole tenor of his speech was that the employment service from unemployment insurance should be kept independent. I did my best to present the other side of the picture. Interviewer: Well, wasn't there also a demand coming from the States because of the nature of their administrative setup that something needed to be done on this? Mr. Murray: I don't recall it. Because you see, in the States we recommended that from the beginning they put the two services together. And the States did. I think, there were only one or two States where they kept the two separate. Arizona, I think was one, and Wisconsin was already under the industrial commission and the unemployment insurance administration has always been rather separate. But I think it was only at the national level that this was really considered an issue, and maybe partly the States didn't know much about it. They just took our word for it that they ought to be together. And there was for some time no apparent friction. Of course, the employment service bounced around so, that I would say that things did not begin to jell on this until after the war. As you know, the employment service was nationalized during the war. When the employment service people came out of the war there was a feeling then that they ought to be kept separate; the employment service people felt this way. But, on the other hand, Altmeyer felt very strongly that the two ought to be together. He went all out on the thing and they were brought together in the Social Security Administration, and then the next year were transferred back over to the Department of Labor. And after that, with budgetary stringency there was an increasing feeling on the part of the employment service that they got the short end of the stick. The Employment Service personnel were constantly shifted to taking unemployment insurance claims. Therefore in the last few years there's been a definite move toward, not complete separation, but separation particularly in local offices. And I understood this has happened in Great Britain, too, or at least they're pressuring for the same thing. Interviewer: Well then, in '37 you say you sort of felt that your mission was accomplished. What happened then? Mr. Murray: Well, Altmeyer called me in his office one day and said that they were organizing the Analysis Division in the bureau of Old-Age Insurance; he would like me to go over there. He knew I was feeling sort of at loose ends. Well, I was plenty busy. I was still working on administration, but Interviewer: Some of the challenges were pretty well - Mr. Murray: And, at that time the idea was that the Analysis Division would engage in administrative research of the Social Security Board because the Bureau of Research was fully organized and was already doing the planning work on old-age insurance legislation. Interviewer: So what did that really leave you then? Mr. Murray: Well, it left me first statistics. Nothing had been done in the statistical field, and we recognized that the information coming in through the administrative process of old-age insurance was going to be a gold mine of information on employment and wages, as well as being useful for administrative purposes. We organized our Statistical Division with the view of the broad usefulness of these statistics rather than conceiving it narrowly as a means of assisting administration. So from the beginning we planned to get out comprehensive statistics. Then on the actuarial side there was the Office of the Actuary, W.R. Williamson who - Interviewer: This was at the Board level? Mr. Murray: Yes, and Williamson was, I think, rather resentful of our doing anything, but eventually we worked out an understanding that the Analysis Division would carry on short-time actuarial estimates so that we'd know what our budgetary needs would be and staff needs and also short-range estimates for the annual actuarial report of the Board of Trustees, and the rough dividing line was that we made the five-year estimates and they made the long-range estimates. Interviewer: How about - was the same attempt made with the Bureau of Research and Statistics? That is - Mr. Murray: I would say that I immediately began to have conferences with the people over there and discussed legislation, but the Bureau of Old-Age Insurance had started out on legislation when I arrived and had already built up a number of technical amendments that were found necessary as they set up the administration. The amendments were on such things as whether an employer paid taxes on the basis of "wages paid" or "wages payable" and questions of that kind. When I arrived over there they already had a draft of a bill -- Interviewer: There was some personnel, too? Mr. Murray: Well, Harry Weiss was over there as sort of a special assistant to the Director who had been working on this, and he was assigned to me and worked as my special assistant on this. We didn't set up any legislative division, but my primary interest was in legislation and so we got progressively into it. So, by the time I left, we were working on legislation. Then we organized a section for administrative research and brought in - oh, what was his name - he went with Budget Bureau later, and he made a comprehensive administrative survey of the Accounting Division which the boys over there didn't particularly appreciate. They were rather jealous of their prerogatives and here's an outsider coming and prying into what they were doing. Joe Pois was his name. He went later with the Budget Bureau, an excellent man, but the fellows in the Accounting Division felt he couldn't begin to know the problems from the point of view of day-to-day operations, so he didn't have a great deal of influence. And so this administrative research sort of petered out, particularly as the Operating Divisions, Field Division, and so on, got their own men to do their own stuff. Interviewer: What part for example did you play in the '39 Amendments? Mr. Murray: So far as broad policy is concerned, I didn't have a great deal to do. I sat in on the whole thing. Interviewer: Maybe you ought to go back one step, what about the Advisory Council? Mr. Murray: Well, that's what I was thinking about. It started meeting in 1938. At that time the Bureau of Research and Statistics still had the primary responsibility for legislation so they did most of the staff work for the Council and pretty much prepared the legislation for 1939. I think part of this was due to the fact that Seidemann, for long as he was Director of the Bureau, was primarily interested in administration. Then Hodges came in who never really took hold at all anywhere. Then John Corson when he came in - I think he probably came too late to get much into legislation. And he at first was primarily interested in administration, too. But then after the 1939 Amendments were passed - I don't remember whether it was just one of these gradual processes but anyway we got into legislation by doing a job. Interviewer: How large were you by that time? How large a force did you have by that time? Mr. Murray: I would say we developed a force of about 125 people by the early 1940's. And most of these were in statistics and in the actuarial section. Interviewer: Did you have the classification then? Mr. Murray: Industrial classification, yes. Interviewer: That was Miss Hine and Bill Cummins? Mr. Murray: Yes, Bill Cummins was with me. The way we were organized at that time, we had difficulty in figuring out where to put legislation. I should have just cracked down on this, but we had set up the Administrative Research Section became more of a program research section and there were some people in it who were interested in legislation. And then John St. John, the Actuary, was very much interested in legislation and was pulling and hauling between him and Jacob Perlman who was in charge of the Administrative Research Section. Well, anyway, they were pulling and hauling as to who would do the job on legislation. I tried to parcel it out, but there was a lot of friction. As long as I was there we never really solved this because you really can't parcel out legislative planning piecemeal. But we did reorganize. And Jake Perlman who had been brought in to the administrative research, had developed that more into the economic research division and he took over most of the legislative planning. In the meantime, John Corson - beginning in the early forties - conceived the idea of what we called the developmental program. Interviewer: What was that? Mr. Murray: This was primarily to do basic research in the areas in which there might be legislative improvement. So we set up a section on coverage which made studies of the problems covering agricultural workers, domestic servants, and so on. Then, we developed chapters on the benefits and eligibility conditions and so on. We had this all mapped out so that eventually we covered the whole area of the program with a developmental report on each aspect of the program, - some 15 or 20 studies which were very, very dull and done over and over -- the studies took 4 or 5 years, more or less. Interviewer: That sounds like much broader than what you started with. Mr. Murray: Oh, yes. Interviewer: So, as the years went by, you took in a larger area. Mr. Murray: Yes. I would think mainly in the field of program planning and legislation, which the Analysis Division has largely gone over into. Interviewer: Did that run you into any problems with the Bureau of Research? Mr. Murray: Well, as I say, they kind of gave up the ghost - Interviewer: I see. Mr. Murray: And particularly after John Corson thought I should be handling this and we just had it figured out and we went ahead and did it and pretty soon we'd done so much research they didn't have much to contribute. The other thing - and this I'd say Jake Perlman had a great deal to do with - was to develop our statistical program. We developed the 1-percent sample of continuous work histories. Interviewer: How did that begin? Mr. Murray: We were always up against the situation that we were handling statistics as of a given date and here was a program that dealt with a man's lifetime. So, if we really were going to get any meaningful statistics to do long-range planning, we needed to know what the continuous work history over a period of years of a representative group of the covered workers. So we set up this 1-percent sample. Interviewer: When was that, do you recall? Mr. Murray: That must have been about 1943. Interviewer: And that was under Perlman? Mr. Murray: That was under Perlman. Interviewer: Was that something new? Nobody else had ever used anything like that? Mr. Murray: Well, no, I don't think so. This continuous work history sample I think was an original idea. Of course, sampling was well established. We figured we could have a small sample of this enormous coverage, so that it was manageable. Interviewer: You were going to say some of the next area that you - I think I interrupted you. You were talking about another area that you covered. Mr. Murray: Well, then another area that we got into was - it felt that if we were planning on benefits, to be realistic we ought to know what was happening to the claimants, how they were being able to get along on their benefits. So we began to make sample studies of beneficiaries. This was very exacting and detailed work and expensive work, but we did make a few studies in some selected cities. I don't know whether they are still continuing those studies or not. We didn't get near as much as I hoped out of them partly because the development of the questionnaire, the interviewing, the tabulation, and the analysis of the data took such a long period that by the time you got the results, things had passed on. It was felt that the material wasn't of great use. Of course, that's one of the constant problems, I think, in this area. One thing I should say is that in the field of legislation beyond these developmental reports - Interviewer: I was going to ask you what were they actually put out for? Mr. Murray: Well, we used them as a basis for developing recommendations for legislation. I would say the last year or so that I was with the Bureau, I spent 50 percent of my time on legislation. I was constantly on the train with Oscar Pogge going over and having conferences in Washington on the development of bills. This was a war period so we actually got no legislation during that period, but I think we laid the groundwork for a good deal that did happen in the 1950 Amendments. Interviewer: I noticed that I think it was in the forties that the State Department first set up that postwar idea of having programs, and there was a subcommittee, interdepartmental, cabinet, and agency-wide, of developing labor standards and social security was a -- Mr. Murray: Well, there wasn't -- Interviewer: I think that was about in '43, '44. Mr. Murray: I don't recall a great deal of that. We had extended conferences with Murray Latimer of the Railroad Retirement Board about coordination of the railroad system. We had conferences with Civil Service Commission on coordination with the civil service system. But, so far as feeling that we needed to do any postwar planning in the way of readjustment or adjustment - you might say - to a peacetime economy, we didn't see that there was a great deal we'd have to do in our long-range program. Now, in unemployment insurance they did. They foresaw a possibility of widespread unemployment and they would have to prepare for that. There was a good deal of postwar planning there, but -- Interviewer: You were saying there was another area, too, besides legislation that the Division undertook. It was pretty large by that time? Or had the war -- Mr. Murray: What I was saying there was -- we got into not only these developmental programs but into active legislation; but beyond that I don't think at the moment of any other areas that we went into. We didn't have a large staff. When I left, I guess we had about 150 people. Interviewer: What were your relations with other outside agencies, particularly those with whom you dealt in order to secure data and that, - examples Mr. Murray: Of course, at that time there was the National Statistical Board. Interviewer: Central, wasn't it? Mr. Murray: Central Statistical Board, which I guess was pretty much displaced by the Council of Economic Advisers. We had to get all our forms approved by them, our statistical forms. Bill Cummins was on the Committee on Industrial Classification. I think we also had a committee on occupational classification that I sat in on. We realized this was too big a job to try to get occupations, so we sort of backed out of that one. But, of course, industrial classification, - we felt quite strongly that we ought to be in on this. Now one thing, we had a great deal of trouble getting was our 1-percent sample, or any statistics classified by industry because we couldn't sell the Board on the fact that we needed it. They said it could make no difference in our costs. We were not going to have a variation of rates by industry. Why do you need industrial statistics? Well, we said that they were just valuable in themselves. This is administrative research, - why are you doing this? So, poor Bill Cummins had an uphill fight. He is still having it, I guess. He needed a good big staff to classify all of these employers and keep up with it. Also, not only that, but this Industrial Classification Committee was constantly revising its coding, so that there was a problem of converting from one code to another so he had to have a good deal of staff, in fact, I guess at that time it was at least one-fourth of the Analysis Division staff. So, I was always on the defensive -- The Board kept asking, "Why are you spending all this money for the budget of industrial classification?" Interviewer: Looking at the whole period, what would you say as Director of this Division were its major accomplishments? Mr. Murray: As I look on it, I feel the establishment of the 1-percent sample, the developmental program - although maybe it just gathered dust - it did contribute to basic research; and third, the beneficiary studies. Interviewer: What were those? Mr. Murray: Those were the sample studies of actual beneficiaries. Interviewer: In other words, sort of a life history you mean? Mr. Murray: No, what they did, they went out and endeavored to see how well these people were able to get along on their benefits, what their family situation was, what other resources they had, and so on. There was a series of articles published in the Social Security Bulletin I guess for a number of years on the basis of these studies. I don't think that they ever had much practical effect. At least they gave you a little more feel of the problems of beneficiaries. I went out and did some interviewing myself and it gave me more of a feel for the people I was working for. Interviewer: What would you say was some of your major crises in the Division? Mr. Murray: I'd say the constant crisis - at least, over the last few years I was there - was over getting a proper organization in the Division, and - Interviewer: Was that - you mean difficulty getting approval or difficulty recruiting personnel? Mr. Murray: No. The difficulty was really we had some very strong personalities as Section Chiefs who had their own ideas. Alvin David used to tell me for years that "You're too nice a guy, you let these guys fight instead of cracking down and telling them that this is going to be it." In fact, John Corson I guess told me that. Interviewer: Well, I guess the very nature of the work though in the way - Mr. Murray: Well, here you've got a bunch of professional people, each of them working with his own ideas. John St. John left before I did. He turned out to be very conservative and, I guess, increasingly had less and less sympathy with the program, to where he didn't feel comfortable and got out. And Jake Perlman had very decided ideas from the standpoint that essentially the problems we were dealing with were economic problems rather than actuarial problems, so he ought to have more say. It was a matter of temperaments, I suppose, more than anything. Interviewer: Do you think some of all of this was due to the fact that the lines weren't clearly drawn? Mr. Murray: Yes. But the whole battle was over legislation. -- I should have just set up a legislative division and put Alvin David in charge of it, and the problem would have been solved. Interviewer: Well, did the organization sort of grow like topsy? Or - Mr. Murray: Well, no, you see, we started out with a Statistical Section, an Actuarial Section, and an Administrative Research Section. There was no room for legislation. What I should have done was set up a Legislative Section when we had responsibility for that. Instead I tried to compromise and negotiate between the Actuarial Section and the Administrative Research Section, which developed more into the Economic Research Section. Instead of, as I say, just cracking down and saying this is the way it's going to be, I tried to get agreement and never could. Interviewer: Well, after you left in '45, you went with the war time agency and then to - Mr. Murray: Actually they wanted somebody to head up the social insurance branch of the Office of Military Government in Germany. Interviewer: What was that supposed to do? Mr. Murray: It had a twofold job. One was to negotiate in the Control Council to try to legislate. Now, on this German assignment, - they organized the military government in Germany to have units and divisions covering the waterfront of all the functions of the German government. Since Germany was divided into four parts at that time, there was this Control Council which attempted to legislate for the country as a whole, since the whole idea was the unification of German. And this went down through echelons to where there was a social insurance committee in the Manpower Division. At that time, with Germany shattered, there was a spirit of "let's start over and do it right this time." There was great sentiment for having a unified social insurance system. And we attempted to negotiate this in the Control Council. The idea was to have one tax covering all types of social insurance, and Germany did have every type of social insurance. One thing that facilitated this idea of unification was they had no reserves -- they had been wiped out. We got nowhere in negotiations. The Russians were always finding objections to everything. You know, you'd think you'd got an agreement and the next week the signals were changed and you would start over again. And, in the meantime, they were working with their own Germans. And I think along about the end of '47, or early in '48, they just made a fait accompli -- produced a unified social insurance system for East Germany, by order, and we were caught holding the bag. In the meantime in the western zones, the Germans themselves had gotten more on their feet and feeling more of their own oats. And also I think bureaucracy had raised its head again to where the spread of unification had largely disappeared and it was a matter of rebuilding the old institutions. Interviewer: What happened in the period when you were here until this, was there a system? Mr. Murray: Oh, yes, the Germans were amazing the way that they got things going again. Interviewer: So what role then did you - Mr. Murray: Well, actually, I don't think we made much of a contribution really. Interviewer: Are you speaking of yourself, the French and the British? Mr. Murray: Yes, each of us operated differently. I'm thinking of myself. I had a staff of about a half-dozen experts. But the Germans knew so much more about this than we did and had such long experience that I don't think we contributed much to it. We did a little bit in making it possible for their communications to cross the lines of the Russian Zone, for instance. The records - you see, in the old days the insurance system in Germany had a separate system for the salaried workers. Their office building was in the British zone, so we facilitated correspondence between that and our zone. In the case of workmen's compensation funds, most of them had their head offices in Berlin, but cases scattered all over the zones. And again, I had an expert who spoke German well who worked with them and helped them to get things moving where there were any problems. I think about the only field in which we actually accomplished anything was with the unemployment insurance system, which had been shattered under Hitler. The only payments went to workers when factories were bombed. They had emergency payments to help rebuild the factory. And so we worked with the British and established, before I left, a joint (although there were separate zones) a joint unemployment insurance system for the British and American zones. The French were rather independent at that time. We weren't able to work it out with them although we had good cooperation in Berlin. They had wonderful Frenchmen there. The people down in the French zone were a little exclusive. I think they felt largely in terms of that their zone belonged to them -- was part of France. So, I don't think that we accomplished a great deal except, perhaps, the Germans felt that they had some place they could go to to get information or get things done. But we were amazed at the way they were able to reorganize and get going again. Interviewer: The records were - Mr. Murray: Well, they had their old-age insurance records on a regional basis, one of the regional offices in the American zone was completely bombed out. So all they did was take the word of the people. The claimants would come in with their papers and show that they had been getting a pension of so many marks and they continued to pay them. And then, they did an amazing job, I think, of taking over the refugees that flocked in from Poland and Czechoslovakia -- those people had no records; everything was taken away from them or they fled without anything. The Germans would take their word for it -- what their status was in the other country to provide them with benefits. We tried to negotiate with the Russians to get records but never succeeded. Then I spent a brief time, three months, down in Greece. I should put on the tape that when I first went over to Germany, George Bigge, one of the members of the Social Security Board, went over with me. He stayed for six months during which we sort of set up basic policies, then he left me in charge. Then, in the spring of '48, I went down to Greece on the request of the American Mission for Aid to Greece which was helping the Greek government at that time get reorganized and going. William Mitchell came from Washington and we worked with the Greek government. The problem we tried to solve there was, although they had a comprehensive social insurance institution, so far as old-age insurance was concerned, it permitted contracting out of existing insurance funds and there were something like 165 industry funds in operation when we arrived, running from 8 people to 50,000. It was ridiculous hodgepodge of plans and we drew up a master plan which the Greeks paid lip service to. Then we worked out an arrangement that an American could come in as an Executive Director of the Institute to reorganize all this. And Oscar Powell had been Executive Director of the Social Security Board. Interviewer: Powell? Mr. Murray: Powell - went out with the area manager of old-age insurance from Chicago - what was his name - (Brannon?) Interviewer: It escapes me at the minute -- Mr. Murray: I think he is in your office in Baltimore. Anyway, the two went out and he told me afterwards that after two years, he didn't feel he had accomplished a great deal, - especially in these pension funds. That was one thing I think that defeated the Clark Amendment under the Social Security Act and was really very fortunate because old-age insurance would be a mess in this country if they had ever allowed contracting out of individual funds. Interviewer: Anything else, Mr. Murray? Mr. Murray: No, I think not - |